Rediscovering the lost art of discussion

As our body politic and the national conversation devolve into the absurd, artists Michael Stearns and Edith MonDragon (MonDragon Fine Arts) present Public Discourse in San Pedro—a provocative exhibition that transforms discussion into art.

Stearns comes from a political family so the idea of talking about issues is not uncomfortable to him.

“My folks and my brothers and I love to discuss, and if you’ve ever been around my brothers and I, you’ll find that we still continue that.”

The exhibition is on view at Michael Stearns Studio in San Pedro, now until Sept. 20. Together, the works in this exhibition, whether through stark imagery, reclaimed materials, or symbolic forms, confront the tensions of our time with equal potency. In an era of conflict and division, Public Discourse asserts art’s unique capacity to translate raw emotion into collective reflection.

Artists in the show are Phoebe Barnum, Rose C’est la Vie, Dave Clark, Diane Cockerill, Eugene Daub, Anne Olsen Daub, Patty Grau, Donna Herman, Jim Murray, Lowell Nickel, Paula A. Prager, Peggy Sivert (Zask), Michael Stearns, and Mick Victor.

When MonDragon and Stearns began putting the show together, they decided that they would be as open as possible, yet Stearns noted they received nothing from the Trump faction.

“The idea of the show was public discourse, and I thought it would be unlike most of the TV stations, especially the obvious ones, Fox and MSNBC are so politicized,” said Stearns.

What is interesting, Stearns said, is that the show isn’t only about Trump. Most of the show is about overcoming injustice and adding to equality and “that acronym that Trump seems to hate, DEI.”

“I’ve always felt that the artist has an obligation, since I was a young kid, probably because my family loved to discuss and to argue, [initiated] from my dad, who was a debater in college …”

Stearns and his brothers grew up taking different sides in debates. It was about the idea of dialogue, especially without getting angry, the back and forth and attempting to make a point or discuss things in an adult way, he explained.

“I feel there’s an obligation as an artist,” Stearns said. “I look at what we do as a recording, as a notation, a monument. Part of our obligation as creatives [is] to have people cast a look at what we see, and maybe tell a story that might cause people to stop and think a little bit. Doesn’t always work, but that’s our obligation, at some level, to try.

“And that’s always been the theory behind this,” Staerns said. “We decided to do it on the spur of the moment. But that’s why we called it Public Discourse.”

What Stearns and MonDragon found (and what the artists talked about in some cases) was not “home-grown anger issues.” It was just as much about the assassinations of journalists in Mexico and the thought of having the courage to stand up.

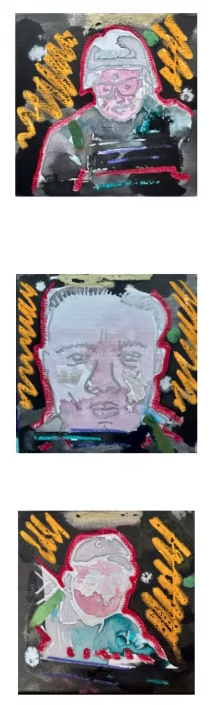

Juri Kroll’s Fake News memorializes murdered Mexican journalists through three haunting portraits. Rendered in dissolving ink and bleeding watercolor, these images of Carlos Ovneil, Lara Dominguez, Gumaro Perez Aguilando, Ceckio Pineda, and others appear as ghosts, slowly fading out of our consciousness, but for the images represented before you.

Stearns noted Resist by Diane Cockerill could describe both sides of the fence (conservative or progressive), but it talks about taking action. Photographer Cockerill’s image depicts a foggy-looking plane, blending shadowy white, blue, and navy, and ‘RESIST,’ written across the top with its letters bleeding in crimson.

Stearns noted he grew up on the Mexican border, looking at Mexican murals, which he loves, just as he loves Mexico, its muralists, and people who speak through their art to social issues.

“You look at Eugene Daub’s piece [Take a Knee] about Colin Kaepernick,” he said. “That’s not politics. It kind of is, but it isn’t. It’s about human rights and about human dignity.”

Image courtesy of Michael Stearns Studio.

In Take a Knee, Eugene Daub’s small, blackened cardboard sculpture reveals flashes of green and red beneath its fractured surface. The kneeling figure’s upraised fist emerges with urgent clarity. The work’s rough texture and hidden hues hold both the grit of struggle and glimmers of resilience.

In VICTIM (War in Ukraine), Peggy Sivert (Zask) layers a New York Times front page depicting a young woman whose dinner is interrupted by shrapnel. The fissures tearing through the collage mirror the fractures of a nation at war, while the work’s title extends to those facing oppression everywhere. A portion of a woman’s face peers back at the viewer. Rough haphazard sutures around her eye indicate both physical wounds as well as those unseen but expressed through her one visible blue eye.

“You look at Phoebe Barnum’s piece [All the Presidents Men] and it’s kind of humorous and yet it’s not,” Stearns said. “It’s very whimsical looking. It’s obviously a caricature of Trump based on an Intuit Indian face.”

In All the President’s Men, the mask base becomes a playground for wispy feathered hair, resembling 47’s coiffure, while tiny plastic men march across the forehead only to end up tumbling down the nose.

“And if you’re okay with that because it benefits you, I get it because this too shall pass,” Stearns added.

“Lowell Nickel’s Chop-Chop Must Stop is a kind of ham-fisted approach to [the idea that] we’ll just chop everything down and start over. That’s the way I look at [his] piece. That’s what people want to do. Many people think, let’s just chop everything down. We’ll go back to the 1940s or 50s.”

Nickel’s piece, which wielded ceramics and wood as weapons against political deception, could be seen in various ways. Axe heads made of clay hover over broken wooden branches. This forest under siege metaphor mirrors democracy’s fragility, in both warning and resistance.

It was the late 1950s to 60s when Stearns attended college, and he said most people his age would say, “‘I thought we did this. I thought we were past all of this,’ and lo and behold, we learned that that’s not true.’

“That’s another reason why we have to have the courage to have a voice,” he said. “Young people are well aware of that, especially when dealing with sexuality and gender issues. They are a lot more comfortable with that. Some of our thinking is dated, and it’s a comfort zone for us, and that’s the problem. We find ways to justify our fears; that’s the scary part. Not kind of work our way through our fears, but wrap ourselves in them.”

The show has had a great turnout, Stearns said; his piece titled We the People is “pretty much in your face about what it is.” He said it is one of his better pieces of work. He has seen people tear up over it.

We the People confront the systematic dismantling of constitutional protections. This large-scale mixed media work, displayed in seven side-by-side vertical rectangles, layers fragmented text from founding documents over distressed surfaces, representing the erosion of democratic institutions. The upside-down American flag at the center sits under the Statue of Liberty.

“You do get emotional because it’s a real challenge to what we hold sacred,” Stearns said. “And I think more people here hold our country sacred than we realize… And if we really sit down and talk to one another, about what frightens us and what makes us fearful, we’re not really that far apart.”

“We have a piece that’s very much a propaganda machine [Mechanicals-Preception] … But that’s how we get our facts today … through electronics, through TV, through the computer, of course, through our phones more than anything. And the hard part is discerning what is propaganda from the true meaning of the word, and what is the truth?

Mechanicals-Perception by Dave Clark is a study of influence from found artifacts across eras. These discarded tools of control demonstrate how perception is engineered to manipulate behavior, inviting viewers to interrogate their own vulnerability to constructed realities.

“And the Nazis had a person who, that was his title,” Stearns said, referencing Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda from 1933 to 1945. “So this is nothing new, the idea of having a radio station or a magazine or a TV station that pushes one agenda. I won’t even call it propaganda because even though what they’re saying may mean something to me, to someone else, it’s the alternative truth, but it’s still the same. We have to listen and decide what the truth is if that’s what we’re searching for, and hopefully we are, and hopefully that guides us in our activities.

“And people wonder why we put stuff on the wall and why I think we should be doing art about this.”

Public Discourse is on view at Los Angeles Harbor Arts, 401 S. Mesa St., San Pedro

Studio hours: Saturdays, 1 to 5 p.m. and by appointment

562-400-0544; michaelstearnsstudio@gmail.com