David Calloway’s “If Someday Comes” Traces America’s Unfinished Reckoning With Its Past

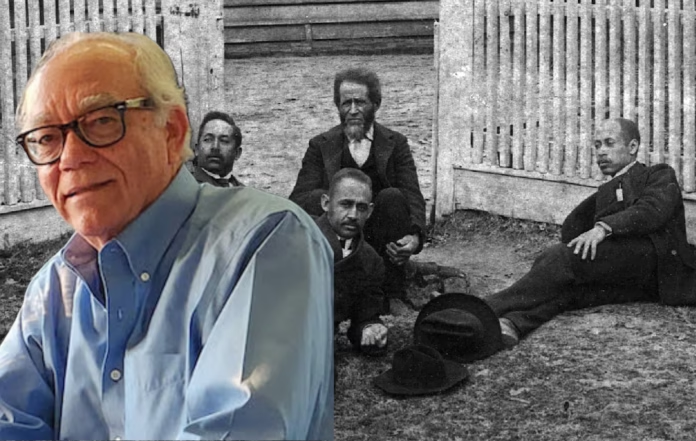

Retired film and television producer David Calloway, a San Pedro resident for more than 20 years, is a modern-day griot — a term of French derivation that describes a class of West African storytellers who preserved the true stories and lineages of their people.

Calloway shares this title with an elder brother, a schoolteacher from fall through spring, who spent his summer breaks traveling the country, chasing down leads on background research, family history, and tracking down distant relatives with even a bit of information to glean.

Calloway didn’t know he was a griot, but he had been steeped and marinated in his family’s oral history from birth, the stories becoming as real as flesh and blood.

Calloway’s career, when read in linear fashion, sounds like a blueprint of my television viewing habits in the 1980s. In our household, I had to complete my chores before my parents came home from work. So between washing dishes, vacuuming all the carpets, and wiping down all the mirrored furniture so that not a fingerprint or a smudge was visible, I was watching all the after-school cartoons from Looney Tunes to Tom and Jerry, from He-Man to Battlecats on one of the two televisions in the house. One in the living room, the other in my parents’ bedroom.

My father was usually home by 5:30 in the evening, and that meant the living room television would be turned on to Monday Night Football or a Lakers game. My mom returned from work by 7:30 in the evening. So that meant I got to slow walk my chores as I took advantage of my television privileges when and where I could, watching all the pre-prime-time shows from CHiPs to Three’s Company. Calloway’s shows largely aired during prime time, during hours I couldn’t watch television.

Calloway got on the ’80s primetime soap opera Falcon Crest as a cinematographer in 1981. He worked on the Freddy’s Nightmares series from the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise, a franchise I watched mostly on VHS, but not the series on television that I could remember. Nash Bridges and The O.C. were shows I heard and read about on occasion in the newspaper. Calloway worked on Dark Justice for CBS and eventually wound up as vice president of production for WWE, which had its own film and television studios. While there, he made 10 films in three years.

And then his wife and children decided it was time for him to retire, he revealed during a May 6 interview with Random Lengths.

Calloway’s retirement freed up time to pick up where his brother left off when he died and document a pivotal moment in his family’s history. It was the story of his great-grandfather, George Calloway, an enslaved Black man in Cleveland, Tennessee.

Calloway recounted this story in the book, If Someday Comes, a historical fiction that is 80% fact, based on oral histories, journal entries of his ancestors and their contemporaries, news clippings and historical reference sources. About the only fictional thing was the dialogue.

Calloway’s story struck me as a perfect Juneteenth feature, an idea that became more important to me after my conversation with San Pedro’s own Maj. Gen. Peter Gravett about the erasure of Black progress as we headed toward Memorial Day. Both Gravett and Calloway are among the featured authors at RLn’s Ink UnChained Black authors event on June 20.

Calloway explained that one of the biggest pieces of information that pulled his book together was when his brother found cousins in Washington, D.C., who still had the family Bible with the inscribed names, birth dates and locations of their ancestors beyond the 1860s.

Calloway was able to build upon this research to write If Someday Comes, which focuses on the years leading to and through the Civil War. The story depicts the divided political climate, propaganda and social decay that led to war before the first shot was fired.

He shows how laws tightened around both enslaved and free Black people, and how division fractured families and businesses. This history, he argues, must be understood to move the nation forward.

In the last edition of Random Lengths, James Preston Allen connected Memorial Day’s radical origins — rooted in grief and desire for national reconciliation — to traditions like the 1865 Charleston ceremony led by freedmen and abolitionists, as well as efforts of the Ladies Memorial Association in Georgia. The federal government credits that association with inspiring Gen. John A. Logan, a Union veteran and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, to issue General Order No. 11 in 1868. Logan called on Americans to decorate the graves of the Union dead “with the choicest flowers of springtime.” Memorial Day was born in that spirit of remembrance and unfinished reckoning.

Calloway believes the Civil War’s end should have marked a true reset, grounded not in false reconciliation but in truth and reparation. Instead, the nation clung to the lie of white supremacy, which enabled the Southern Strategy, the Ku Klux Klan, the Tea Party movement, and, ultimately, the Jan. 6 insurrection.

“It saddens me to see so much stereotypical dislike, even bordering on hatred, for people who are ‘not like us,’” he said.

Calloway’s great-grandfather was legally chattel to his biological father, yet was taught to read and write and trained to manage the family’s farm and business. George’s biological father and master thought it was cheaper to have someone in-house to do the job than to hire an overseer from outside. George and the rest of his enslaved family were active in the anti-slavery resistance movement, better known as the Underground Railroad. After emancipation, George ensured his children were educated — an act of resistance and legacy. For Calloway, education remains the clearest path to equity.

On education, Calloway noted that George’s three surviving sons all graduated from Fisk University, establishing a tradition of education in his family.

“So we are either teachers or professionals,” Calloway explained. His great-grandfather established a pathway to freedom for the rest of his family by saying, “This is how you’re going to live your life,” Calloway explained.

“My father used to say to me that the one thing they can’t take from you is what you’ve learned in school. So, ‘You’re going to get an education’ was the family motto,” Calloway said.

Calloway referenced President Lyndon B. Johnson’s discussion about poverty among the people in Appalachia, and explained how those people were just as broken and exploited as enslaved Blacks.

“It’s just really a phenomenon of how this country works,” Calloway said. “We need to make amends.”

Calloway said reparations are one of those things people talk about a lot, but he doesn’t believe the United States, under any administration, is going to write me, him, or any of our children a check we can cash.

“That’s not going to happen,” Calloway said. “But what could happen is that the country could recognize its obligation to the Aboriginal Americans from whom they stole the land, and the Black Americans from whom they stole their lives and labor. And the poor working whites who were worked to death in coal mines.”

He blames today’s political climate on Ronald Reagan, who, Calloway argues, mainstreamed the idea that government is the enemy — a legacy now weaponized under Donald Trump.

“What we’re seeing today is some combination of that,” he said. “‘Cultural elite’ is just code for educated people with real opinions, and that clashes with traditional structures of power.”

Citing journalist Anne Applebaum, Calloway said constitutional rights have often been ignored at the local level — from Wilmington (North Carolina) to Tulsa (Oklahoma) — whenever power felt threatened.

“I’ve had to give that a lot of thought,” he said. “I don’t think it’s black and white. It’s grayscale, like everything else. But I think there’s truth in that point of view.”

And that truth — uncomfortable, complex and long buried — is what we must confront if we are ever to finish what the Civil War attempted to complete: the work of becoming a more perfect union.