Sept. 16, By Nolan Higdon

“The US election is approaching, and with it a crescendo of anxiety about online lies,” declared an August 2024 Financial Times article. Indeed, over the past decade, the weaponization of fake news by political figures such as Donald Trump, proponents of the Brexit vote, and during the COVID-19 pandemic have heightened fears about misinformation. These concerns led social media companies to moderate content, prompted governments such as the US to create boards aimed at curtailing disinformation, and resulted in academia establishing positions for disinformation experts.

In response, news outlets have unveiled new systems for documenting the lies of elected leaders. This response from the press begs the question: given that documenting the lies of elected leaders is part of their job description, why weren’t these common practices prior to the 2016 election? Worse, many of these systems, such as the Washington Post’s documentation of all the lies from the president were abandoned after Trump left the White House. Regardless, history and research suggest that rather than relying on the press, corporations, or governments to combat fake news, it is more effective in a democracy to equip the electorate with the skills and tips to spot false information for themselves.

Given that it is a presidential election year — one marked by numerous events that have fueled fake news, including US support for Israeli attacks in Gaza, campus protests, an assassination attempt on Trump, concerns about Biden’s mental acuity, and the rise of vice president Kamala Harris as a major candidate with less than 100 days before the election—it is critical that the electorate carefully evaluate evidence when deciding how to participate in the democratic process.

What follows is a guide aimed at helping citizens determine the veracity of information. It is not a guide that tells people what to think, but rather, it is an effort to share tips on how to think more critically and independently about the accuracy of information that we the people are inundated by daily.

What is Fake News?

Fake news refers to information that appears to be real news but is baseless, inaccurate, misleading, or false. This can include misinformation, disinformation, hoaxes, lies, satire, and propaganda. The term became widely known when former President Donald Trump used it to label critical news stories about him that he found inconvenient, regardless of whether they were true. Instead of distinguishing Trump’s use of the term from its original meaning, many journalists became frustrated and began avoiding the term altogether.

Who Produces Fake News?

The truth is that anybody can create and spread fake news—even without realizing it. Research shows that some of the most effective fake news producers include:

Governments: Even governments, including the US, sometimes manufacture fake news through so-called false flag events, and use media to spread fake news to gain support at home for a particular action. Indeed, under Operation Mockingbird during the Cold War, the US government via the CIA worked with reporters and news organizations to get their propaganda published as journalism. This practice was repeated in the War on Terror in both legacy and digital media.

Corporations: Companies have spread fake news to protect their profits. For example, the tobacco industry tried to hide the negative health effects associated with smoking; the fossil fuel industry suppressed evidence that showed their industry was contributing to climate change; pharmaceutical companies lied to doctors to maintain access to patients who were addicted to their products; and the sugar industry funded studies to blame fat, not sugar, for health problems.

News Media: Sometimes, journalists and news outlets, trusted for accurate information, publish false stories. This can happen when a journalist wants to advance their career, as seen in the cases of Jayson Blair (New York Times), Brian Williams (MSNBC), Bill O’Reilly (Fox News), Gabriela Miranda (USA Today), Taylor Lorenz (Washington Post), and Stephen Glass (New Republic). It can also occur for hyperpartisan reasons. For example, Democratic-leaning media propagated many baseless and false claims about Russiagate after Trump became president, just as many right-wing outlets amplified the story that the 2020 presidential election was stolen, despite knowing it was false, because Trump and his supporters wanted people to believe it was stolen when factually it was not.

Individuals: Some people spread fake news for their own selfish reasons. For example, Susan Smith falsely claimed a Black man killed her children to conceal that she murdered her children. Similarly, Alex Jones fabricated wild stories about 9/11, “gay frogs,” and the Sandy Hook tragedy in order to nudge people to purchase his products.

Fake news can come from many sources, and it is important to recognize that we all play a role in stopping its spread.

What is the Harm in Disinformation?

Like any type of information, disinformation is not necessarily harmful unless it is accepted as true and acted upon. It is worth reminding the reader that disinformation is deliberately false or misleading. Indeed, the danger of fake news as disinformation is that it can convince otherwise good people to take aggressive and dangerous action. For example, the fake news story about how Senator Ted Cruz is the Zodiac Killer is somewhat humorous, but not dangerous, unless someone acted upon it. The problem is that fake news convinces users they are morally just in their actions. For example, rioters on January 6, 2021 believed they were protecting democracy; and the father who shot up a Pizza restaurant in Washington, D.C., thought he was liberating victims of child abuse. In both cases, the actors were convinced by fake news stories that they were doing something altruistic.

In other cases, authoritarian regimes act in bad faith to use fake news to create an “other,” dehumanized group to foster a sense of unity and fear among the populace, such as was done Nazi Germany. It is in moments such as these that people may be willing to sacrifice civil liberties for security which further empowers the regime because they do not have laws or a free press preventing them from ignoring human rights. Additionally, false information can convince voters to act against their own interests or support morally and ethically unsound policies or processes.

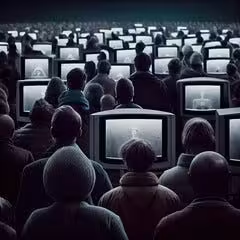

Did the Internet Cause Fake News?

No. Fake news has been around for a long time, but studies show that the economic incentives of the internet enable false information to travel further and faster than truth. The internet is not alone as every new technology has brought new ways for fake news to spread. For example, early photographers staged images to create fake news, and a radio broadcast once convinced some people that aliens were invading Earth. With the rise of television, staged events, such as paid actors protesting, could be broadcast to millions. Today, the internet and artificial intelligence (AI) have made it even easier to create convincing fake news. AI can produce realistic-looking images, videos, and audio, making it harder to discern what’s real and what’s not.

Why Can’t We Just Censor Fake News?

Censorship is not a solution to eradicating fake news, it is a step toward authoritarianism. Entrusting an individual or institution to eliminate fake news empowers them to be the arbiter of truth. They have as much as ability as anyone else to spot fake news, so why give them the power? Furthermore, many powerful entities – such as governments and corporations – would love for the public to entrust them to determine the veracity of information because then they can categorize their fake news as truth, or censor true stories coming from those with different but factual perspectives. Indeed, rather than get lost in a debate about which content should be censored, ask yourself if you trust the government, corporations, or any individual to not abuse that power and only censor demonstrably false content? You should not trust them. Whether intentional or not, they can and have incorrectly categorized content as false that they later admitted was true such as with the Hunter Biden laptop story or the existence of a debate among scientists about the origin of the Covid-19 pandemic . As a result, it is best to oppose censorship in any form regardless of content being targeted for moderation.

Will AI Save Us From Fake News?

Artificial intelligence is vastly different from how it is presented in the movies. Today’s artificial intelligence is not sentient, so it is more like what Meredith Broussard called “artificial unintelligence.” It is a tool that can certainly make some tasks easier or completed more quickly. However, it is not a substitute for critical thinking or written communication (to write well is to think well). Rather than being a sentient being, AI is tool that is designed by humans to follow the directions of humans. However, the industry advertises AI as being of equal or greater intelligence than human, which is why so many people suffer from what Gary Smith calls the AI Delusion: the belief that AI is an infallible savior. From the data that it depends on and the engineers who tell it what to do, AI reflect the bias of its human creators. That is why we find AI to have subjective views, including racist ones. It has been repeatedly shown that AI chatbots share inaccurate or false information. Research shows it is easy to program AI to spread disinformation, so it may actually be a tool that complicates rather than ameliorates the fake news problem.

What are Some Tips for Resisting Fake News?

Citizens of all ages increasingly get their news online. Unlike in the past, when we relied on television news programs or newspapers, it’s now harder to distinguish between real journalism and other types of media content. Before sharing anything, it’s important to ensure its accurate—sharing false information contributes to the spread of fake news. Here are some tips for citizens as they navigate the information surrounding the electoral landscape:

Resist the Pressure

Don’t feel pressured to care about every trending topic, as it is humanly impossible to be well informed on everything. Still, this pressure can convince people to stake out a position on any given topic. This occurred in 2021, when, after nearly two decades of war, US social media feeds were suddenly filled with opinions about President Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan. It was surprising to see so many people suddenly focused on Afghanistan, even though it hadn’t been a major news or policy topic for years. Shortly after, the same thing happened with Ukraine, and later with Israel and Gaza. People felt pressured to comment and stake out a position regarding something about which they knew very little, when it would have been wiser to investigate and learn about the topic at hand.

Do Not Confirm Your Bias

In the digital world, algorithms show users content that they are most likely to engage with (via likes, shares, comments). This happens because digital platforms profit by keeping users on their screens, using techniques from the gambling industry to keep users hooked. Content that confirms users’ beliefs or stirs up strong emotions like fear or anger can be especially effective. Fake news producers understand this and create content that plays on these emotions, knowing that platforms will prioritize such content. Additionally, platform operators have sometimes been pressured by political parties and governments to prioritize certain content and moderate others, creating a curated experience for users. This has been confirmed by revelations from the Twitter Files and more recently Mark Zuckerberg of Meta. So, before diving into the latest trending topic, ask yourself if you genuinely care about it and are knowledgeable, or if the algorithm is making you care by appealing to emotions and other social pressures.

Scrutinize the Polls

Polls can be a helpful indicator of what the public is thinking at a given moment, but they are a poor predictor of future outcomes. For example, many Trump supporters in 2023 told pollsters they might change their vote if Trump were indicted on felony charges. However, after 34 felony charges, Trump’s support remained steady. This is because polls capture a snapshot in time; they do not predict the future. In fact, the famed 538 from Nate Silver admitted that their forecast method was flawed in 2024. Furthermore, pollsters often have biases in how they collect data, such as relying on “high-turnout voters,” which may miss a surge in turnout among those incorrectly categorized as low-turnout or non-voters. Indeed, pollsters have consistently under-polled Trump and pro-choice voters since 2016 and 2022 respectively. Lastly, polling utilizes statistical methods that always include a margin of error. This is critical because even if a candidate is leading by 2 points, a margin of error of 5 points means that the pollster finds that the candidate can win by 7 or lose by 3.

Be Wary of Selective Editing

Anytime you see an edit in a clip, it should raise concern. It’s important to see content in its entirety; otherwise, it can be misleading. For example, MSNBC selectively cut clips of an episode of Joe Rogan’s podcast to make it appear as if he supported Vice President Kamala Harris in the 2024 election. Only after public protests did MSNBC apologize and remove the clip.

Take Your Time: Don’t React, Investigate Before You Share

Fake news often tries to trigger strong emotions and takes advantage of the fast-paced nature of digital platforms, which push users to share and like without fully understanding the content. Resist the urge to react immediately. Slow down and ask questions before sharing. The digital era is defined by the phrase “move fast and break things.” However, when it comes to determining the veracity of information, moving fast breaks democracy. This already occurred during the 2024 election cycle. Within minutes of the report that former President Trump had been shot at a rally in Butler, PA, the internet was filled with people drawing conclusions—whether it was a false flag, that Democrats did it, that the government did it, or that no shots were fired at all. At the time, no one had enough evidence to support any of these claims. This means at least some, if not all, were false, and by sharing them, users were helping spread fake news. It is much better to be patient, ask questions, and wait for evidence to emerge rather than jump to baseless conclusions that complicate rather than clarify events.

Think of Yourself as an Internet Citizen, Not a Consumer

Many people use the internet passively, simply consuming whatever content algorithms show them. Instead, consider yourself an internet citizen—someone who uses online tools to stay informed and help stop the spread of false information. An internet citizen asks relevant and responsible questions, seeks out dissenting views, and interrogates the media and political system.

Interrogate the Party’s Story

Political parties often create idealized narratives about their candidates, such as portraying someone as a caring prosecutor or a family-oriented leader. While these stories may be appealing, it’s important to dig deeper. Be skeptical and recognize that there is usually more to the story.

The Alarm Bells of Racism and Race Reductionism

There is extensive historical documentation of how fake news fosters racism, such as white women falsely claiming they were raped by Black men or White Americans blaming immigrants for the economic hardships of the working class. These and other “racial hoaxes” are used for a variety of purposes such as dividing the electorate along racial lines. Additionally, faux racism, such as the case of Black actor Jussie Smollett falsely claiming he was lynched by White people, and selective reporting, such as the lack of mention of the racial identity of Kyle Rittenhouse’s victims, can be used by those trying to divide the electorate with polarizing narratives.

Don’t Trust the Headline

Headlines can be misleading or designed to grab your attention, often not fully representing the content of the article. As someone who has written for many publications, I can tell you that headlines are often chosen by editors and do not accurately depict what is in the text. In some cases, headlines are even manipulated by campaigns, as was the case with Harris’s team creating false headlines to boost her image. It is wise to always read beyond the headline.

Investigate Ads and Influencers

Under US law, advertising companies are allowed to bend the truth in a practice known as puffery. For example, they can claim that this is the “best milkshake” or that “this product will attract beautiful women,” even though these statements are utterly subjective, not factually true. However, political advertisements can engage in puffery and cherry-picking of content. Indeed, political advertisements provide the best image of one candidate and the worst image of another. In the digital era, campaigns use “influencers,” who seem like normal people, but are actually paid advertisers for a campaign. Also, note that sometimes parties will create content to support another candidate who they think will take votes away from their primary opponent. Indeed, Democratic Party-aligned organizations have done this with RFK Jr.’s presidential bid this election cycle.

Do Not Believe It Because You See It

Just because something is on a screen doesn’t make it true. Indeed, Fox News Channel has a long history of altering images to make people appear less attractive and inaccurately introducing altered videos to stoke hate and fear of Black Lives Matter protesters. In the digital era, false content is more convincing than ever. For example, “deepfakes” are videos that look real but are completely fake, created using advanced technology. Back in 2016, expert Aviv Ovadya warned about the dangers of deepfakes, saying, “we are so screwed.” Now, these fake videos are being used in political campaigns, like a false image of Taylor Swift fans, known as “Swifties,” wearing shirts that say “Swifties for Trump.” Be cautious and question what you see online.

Verify it is Journalism

Journalism is a vital profession protected by the Constitution and crucial for democracy. However, many people aren’t taught how to recognize ethical journalism. A good journalist uses diverse sources and evidence, has a track record of accurate reporting, and admits mistakes. If you don’t see a variety of sources and/or you see a lot of opinion, remember that is not journalism. A great list of independent sources and the topics they cover is provided here by Project Censored.

Identify Conflicts of Interest

Good journalism aims to be objective, though complete objectivity is very debatable. Nonetheless, conflicts of interest stand in stark contrast to objectivity. A conflict of interest occurs when something about a journalist, author, or publisher could cause you to doubt the accuracy of their reporting. For example, a journalist might be prohibited from reporting on a family member because the personal nature of their relationship threatens to make the journalists biased toward that family member. This issue arose when CNN’s Chris Cuomo reported on his brother, Governor Andrew Cuomo of NY, and attempted to discredit accusations against him. Conflicts of interest can also involve news outlets. For instance, in the early 2000s, MSNBC was funded by General Electric, a company involved in the defense industry in general and in Iraq in particular. Some have noted that this influenced the removal of anti-war voices before the 2003 Iraq invasion. As a result, before engaging with content ask yourself: who owns this outlet? Who funds this outlet? Who is the author? What relationships do the author and publisher, or sources have that could be a conflict of interest?

Make Sure You Understand the Content

Fake news often tries misleading people to believe something that was not actually communicated. Take the time to fully understand a story. For example, an August 2024 headline read, “Exclusive: Harris’ election effort raises around $500 million in a month, sources say.” This doesn’t mean Harris actually raised $500 million; it means sources claim she did.

Pay Attention to Representation

News media sometimes oversimplify or misrepresent identity groups. For example, many in news media assumed that all women would vote for Hillary Clinton in 2016 because she was a woman, but she actually lost the white women’s vote to Trump. Similarly, some argued all Trump voters were motivated to support Trump because he is a racist, but about 10-15 percent of President Barrack Obama voters voted for Trump in that election, so they were not motivated by race alone in their voting. Furthermore, the media often portray Latinx voters as primarily concerned with immigration, but research shows that it is one of many concerns from Latinx voters and may not even be a top priority. Another example is how the media often portray the “working class” as predominantly white and male, even though the working class includes many people of color and women. These representations result from choices made by the news outlet, and they skew the public’s knowledge of the electorate.

How Can I Tell if I’m Being Gaslit?

Gaslighting refers to manipulating someone into questioning their own reality. Wealthy organizations, politicians, governments, and corporations often fund propaganda campaigns that distort public perception. It might take years before we have proof that a shift in public opinion was actually due to propaganda. For example, many people suspected the US government was lying about weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in 2003, but it wasn’t proven until 2005. Similarly, activists knew that climate change was caused by human activity and that the oil industry was spreading doubt, but it took decades to prove. When gaslighting, propagandists will often utilize some of the following tactics:

Change the Facts

Effective propaganda campaigns foster doubt about facts, so people do not know what is true. For example, Donald Trump popularized the false claim that former president Barack Obama was not born in the US, a tactic used to discredit the first Black president. This is similar to recent claims that vice president Kamala Harris “isn’t really Black,” citing misleading headlines that misrepresent her racial identity. These claims are part of a long history of misrepresenting the facts to undermine people of color in leadership.

Discredit an Individual Through Labels

Naming by labeling is a fallacious practice where people label something and rely on that label alone to define the event, person, or action. This oversimplification can seem plausible enough for people to abandon their previously held, perhaps more sophisticated interpretation of the available evidence. However, a label is not evidence. For example, the press frequently used the phrase “hallmarks of Russian disinformation” when discussing the release of Hunter Biden’s laptop in 2020. As it turned out, the laptop was Biden’s, but the press did not admit that until two years after millions of people, who were convinced it was Russian propaganda, had voted in that year’s presidential election. More subtle forms of this occur when the press uses phrases like “the most electable candidate” or describes someone as “presidential” to signal that other candidates are unelectable or non-presidential. These subjective labels are treated in news media as facts, which conditions primary voters to choose the “most electable” candidate so they can defeat the other party in the general election. However, as Hillary Clinton supporters will acknowledge, such terms can lead primary voters to select a candidate for the general election that does not win, which leaves voters wondering if the media swayed them from supporting a more viable candidate.

Shoot the Messenger

When those in power cannot discredit an argument that threatens their power, they will attack the character of the person making the argument. One way to achieve this is by advancing baseless claims of sex crimes. It is important to note that the #MeToo Movement aptly demonstrated what happens when we don’t believe victims: perpetrators can destroy many more lives without being held accountable. It is also true that it is extremely rare for an accuser to lie. At the same time, there is a history, albeit a small one compared to the ocean of legitimate assault accusations, where some accusers (2-10 percent) lie about an assault. For example, there is a long history of white women falsely accusing Black men of sexual assault to justify violence and murder against the accused. Researchers argue that governments—such as in the case against Julian Assange of WikiLeaks—and corporations—such as General Motors’ war against Ralph Nader—manufacture sex crimes charges against people who threaten their power. So, yes, believe every accuser, but also investigate accordingly, and through that investigation, determine if there is any evidence of such a crime or known conflict of interest in why the person targeted is being accused.

Give the Illusion of Establishment Consensus

When it seems like a popular opinion has emerged suddenly, it’s wise to suspect that it may result from a propaganda campaign, especially when you’re feeling pressured to adopt the position. For example, the US support for Ukraine emerged as a seemingly out of nowhere consensus that engendered parades, memes, speeches, and videos. Similarly, for decades, politicians have relied on the “message of the day,” which everyone in the party promotes, hoping that the public will conflate familiarity with veracity. Also, governments and political campaigns have been known to fund studies and promote opinions from various sources with the goal of shaping public perception. For example, Influencers– social media users who appear to be average people sharing a popular opinion, but in reality, they are often paid to share a specific message- are currently being used by the Harris campaign to shape voters’ opinions on social media platforms.

Engage in Revisionism

Voters often assume they misunderstood something in the past when it does not align with what they know in the present. In these moments, I encourage audiences not to assume they are wrong, but to investigate further. For example, in 2024, few people remember that it was actually Democrats, including Kamala Harris, who spread skepticism about the COVID vaccine, only to change their stance once in power, denouncing the unvaccinated as causing a “pandemic of the unvaccinated.” Trump has done something similar, shifting from pro-choice to anti-abortion, to the point of appointing three anti-abortionist judges, and then returning to a pro-choice stance in 2024. These types of switches occur when politicians are trying to curry favor with a particular base and demonstrate that they will say whatever is necessary to win. It’s not that voters misremember the past; it’s that the candidate lacks a principled stance and hopes to say the right thing to secure votes, regardless of their intentions once elected.

Weaponize -isms

One of the big cultural successes of the last decade—thanks to the work of the Occupy Movement, Black Lives Matter, the Sunrise Movement, #MeToo, and Bernie Sanders’ campaigns—has been increased awareness of social justice issues. However, this awareness, sometimes called “wokeness,” can be weaponized against the very people fighting for a socially just agenda. For example, those who claimed that Biden could not win the 2024 election, let alone run for office, due to his declining mental acuity were labeled “ageist.” In fact, they were concerned about his cognitive abilities, not his age. In more sinister ways, focusing on identity at the expense of everything else can conceal non-socially just attitudes and behaviors. For instance, those who criticized Hillary Clinton’s hawkish positions on war were called sexist, as if being anti-war or pro-peace was inherently sexist. Comedian Jimmy Dore commented on this phenomenon, saying, “if it was 1860 the Dems would be bragging about their first transgendered slave owner.” Lastly, isms can be used to quell efforts at combatting powerful institutions. For example, in 2016, Hillary Clinton sought to stifle support for breaking up the banks – an idea popularized by her rival Bernie Sanders – by arguing that “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow….would that end racism? Would that end sexism?” “No!” The implication was that since breaking up the banks did not directly address racism and sexism – although there is certainly a case to make that it would benefit women and people of color materially – we must do nothing.

Foster a Moral Panic

A moral panic refers to a widespread fear, often irrational, that some evil threatens the well-being of society. Fake news is critical in creating moral panics because, when widely accepted, it gives the impression that an insurmountable and growing threat exists. Famous examples include the Satanic Panic of the 1980s or the pharmaceutical industry’s war on sleep medication, which fueled the moral panic over date rape drugs. Indeed, fake news itself became part of a moral panic after the 2016 election, where it was blamed for everything wrong in society—a convenient distraction from the political parties and politicians who had been or were vying to lead the nation.

What are Some Trustworthy Media Literacy Organizations and Resources?

For those who want more information and resources, the US is home to many thriving media literacy organizations. Below, I include those who do great work and avoid the conflict of interest that comes with corporate-funded media literacy—which often works to protect and normalize corporate media.

Project Censored: Founded in 1976, Project Censored’s mission is to promote critical media literacy, independent journalism, and democracy. They educate students and the public about the importance of a truly free press for democratic self-government. Censorship undermines democracy. They expose and oppose news censorship and promote independent investigative journalism, media literacy, and critical thinking.

Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR): FAIR, the national media watch group, has been offering well-documented criticism of media bias and censorship since 1986.

Free Press: Monitors the media landscape and sounds the alarm when people’s rights to connect and communicate are in danger. Focus: Saving Net Neutrality, achieving affordable internet access for all, uplifting the voices of people of color in the media, challenging old and new media gatekeepers to serve the public interest, ending unwarranted surveillance, defending press freedoms, and reimagining local journalism.

Project Look Sharp: Project Look Sharp is a nonprofit, mission-driven outreach program of Ithaca College. Their mission is to help K-16 educators enhance students’ critical thinking, metacognition, and civic engagement through media literacy materials and professional development.

The Park Center for Independent Media: PCIM’s mission is to educate the public about independent media, especially US-based outlets producing content on issues such as equity, social justice, and sustainability. Based at Ithaca College, the center examines the impact of independent media on journalism, democracy, society, and participatory cultures in response to concentration of media ownership, the emergence of conglomerates, and corporate constraints on journalism in the United States.

USC Critical Media Project: the Critical Media Project (CMP) is a free media literacy web resource for educators and students (ages 8-21) that enhances young people’s critical thinking and empathy and builds on their capacities to advocate for change around questions of identity.

Critical Media Literacy: Engaging Media and Transforming Education Library Research Guide: Jeff Share, PhD., of UCLA has put together this amazing repository of resources for teaching and learning about critical media literacy education.

Prop Watch: The Propwatch Project, the world’s first visual database of propaganda techniques, is a nonpartisan, educational non-profit launched in 2018, dedicated to raising public awareness of propaganda and disinformation.

The Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ): SPJ is the nation’s most broad-based journalism organization, dedicated to encouraging the free practice of journalism and stimulating high standards of ethical behavior.

Verity: Verity is a free news site created by the Improve the News Foundation (ITN), an apolitical American non-profit. It aims to counter misuses of artificial intelligence that have resulted in a distorted online news environment, where alternative facts often overshadow scientific truths, and fractured narratives contribute to social discord.

Conclusion

The only people who should have anxiety and concerns over “online lies” are the people making and spreading them. The radical idea of democracy is that the people can make decisions for themselves. They do not need the lies of the powerful or moderation from Big Tech or government overlords to maintain a thriving democracy. The people can, have, and will forever be able to make critical decisions about their future. False information is a reoccurring nuisance, but it is not an insurmountable challenge to representative democracy when we have the critical media literacy curriculum and educational programs available to address it.

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to Lorna Garano, Mickey Huff, Reagan Haynie, and Mischa Geracoulis for their invaluable edits, feedback, and unwavering support in the creation of this guide for spotting fake news. Your contributions have been instrumental, and I am deeply grateful for your time and expertise.

Nolan Higdon is an author, lecturer at Merrill College and the Education Department at University of California, Santa Cruz, Project Censored National Judge, and founding member of the Critical Media Literacy Conference of the Americas. Higdon’s areas of concentration include podcasting, digital culture, news media history, propaganda, and critical media literacy. All of Higdon’s work is available at Substack (https://nolanhigdon.substack.com/). He is the author of The Anatomy of Fake News: A Critical News Literacy Education (2020); Let’s Agree to Disagree: A Critical Thinking Guide to Communication, Conflict Management, and Critical Media Literacy (2022); The Media And Me: A Guide To Critical Media Literacy For Young People (2022); and the forthcoming Surveillance Education: Navigating the conspicuous absence of privacy in schools (Routledge). Higdon is a regular source of expertise for CBS, NBC, The New York Times, and The San Francisco Chronicle.

Details: https://nolanhigdon.substack.com/p/a-brief-resource-guide-to-fake-news?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=1418461&post_id=148925525&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=17catr&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email