Marcus Garvey and Rev. James E. Lewis’ Parallel Visions of Black Liberation

This is the fourth story of the Hidden History of Black San Pedro series: Rev. James Lewis, an immigrant who made his way to San Pedro from Liberia in the 20th century who founded a shipping line intended to foster trade between his native country and the United States and transport millions of African American missionaries to the continent.

Through the turn of the 20th century, Black independence and Black freedom through Black self-determination were goals throughout the Black diaspora since the end of slavery in the Western world. So much so that Black people with vision (men and women alike) were divining the future of Black people around the world for the next 100 years, and were told by their creator that their salvation would be on a boat.

In the Old Testament, God told Noah that a flood was coming. He didn’t tell him when the flood was coming but instructed Noah to prepare. And Noah obeyed. When the flood came, Noah and his lineage were spared.

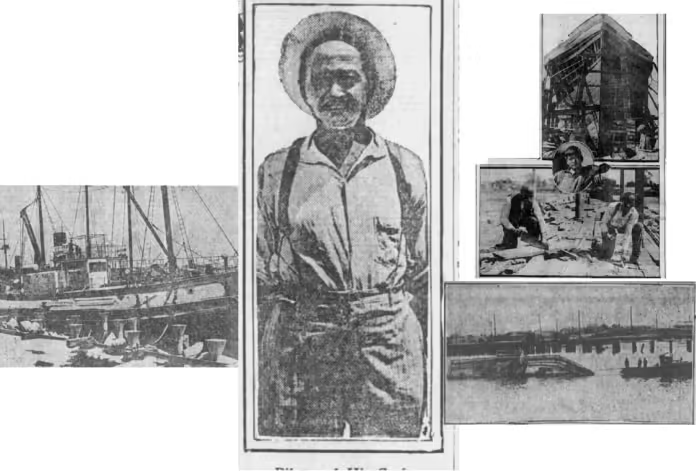

During the first decade of the 20th century, San Pedro Pastor James Edward Lewis started a shipping line called the Ethiopian American Steamship, Freight, and Passenger Colonization Company. He was born in Millersburg, Liberia in 1876, and migrated to the United States Chicago, Illinois in 1893 via Montreal, Canada. By virtue of when he was born and the privilege that allowed him to travel, he saw what time it was. He was a contemporary of Marcus Garvey, a controversial figure 10 years younger than Lewis, but with parallel visions of achieving Black liberation.

They lived in a period in which the extrajudicial killings of Black people were commonplace — a period during which employers reaped the benefits of Black labor. At the same time, unions didn’t want them, even after slavery was abolished in most Western countries and Western Europeans were carving up the African continent like a roasted pig, each snatching ever larger pieces for themselves. It’s not hard to imagine the how and the why they received the visions they did.

On the West Coast, in Los Angeles, the Ethiopian-American Steamship Company was founded to build ships, carry freight and passengers from all parts of the world to Africa, to negotiate for the purchase of lands upon which to establish colonies of Black Christian missionaries, starting with Liberia. Despite his missionary focus, Rev. Lewis built institutions to promote self-sufficiency and self-determination amongst Black folks in Los Angeles and beyond, who dreamed of carving out a place in the world that they could call their own and thrive in.

Similarly, on the East Coast, Garvey advocated for an end to European colonial rule in Africa and argued for the political unification of the continent, envisioning a unified Africa. Although he never visited the continent, he was committed to the Back-to-Africa movement. Beneath the banner of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, or UNIA, Garvey launched various businesses in the U.S., including the Negro Factories Corporation and Negro World newspaper. In 1919, he became president of the Black Star Line shipping and passenger company, designed to forge a link between North America and Africa and facilitate African-American migration to Liberia.

Lewis had migrated to Los Angeles by 1907 and came into the public’s consciousness when the English tramp steamer, Georgia (suggesting that the steamship was old and itinerant), made a port of call at the Los Angeles Harbor in April 1909. The vessel sailed into a reception of about 20 Black Angelenos, presumed by contemporaneous reporting to be stockholders in Lewis’ Ethiopian-American Steamship Company,

The investors inspected the vessel in the outer harbor, where she anchored upon arrival. Lewis and his cohorts initially revealed little about their plans, only that they put $100 down with an option to buy.

The owner of the steamship, the Canadian-Mexican Steamship Company, placed the price at $30,000 (about $1 million in today’s dollars). The promoters of the Ethiopian-American Steamship Company chose not to tell how much of the money had been raised, newspapermen of the time assumed the company’s pockets weren’t very deep. The company sold stock at 75 cents a share in January of that year.

What’s apparent is the reporter heard the would-be investors gasp after learning the price tag of the ship and Lewis’ plans. The preacher told the investors he would capitalize the company at $1 million ($34 million in today’s dollars).

A reporter said he was painting, “Rosy pictures of the possibilities of a steamship line from San Pedro to Monrovia, the capital of the negro republic of Liberia in Africa, have been painted in efforts to Interest members of the race.”

They called Lewis’s plans “a scheme,” one which there had been much talk about in the Los Angeles Black community for several months before the arrival of the Steamship Georgia.

That steamship was not the first vessel on which the Ethiopian-American Steamship Company sought an option to buy.

A local steamship agent negotiated with the owners of several vessels for the promoters. The Ethiopian-American Steamship Company and its investors entertained buying the ship for nearly a year before interest dried up altogether.

The next time Lewis is mentioned in the press is eight years later, after World War I ended. Lewis became a recognized preacher within the Church of the Living God denomination. He had decided to build a concrete vessel on the sand at Terminal Island, choosing to avoid relying upon shipping agents selling used shipping vessels.

He experienced challenges, however, in securing materials. With the help of his wife, Louvenia, Lewis laid the keel and part of the frame. The ship was to be about 80 feet in length upon completion. Lewis claimed to have successfully built eight using this design previously. But local lumber yards declined to sell lumber to Lewis. Managers of local yards where he sought to buy materials told him the boat he was building would never get out of the harbor.

Lewis, who worked as a cement worker for several years before launching this ambitious project, said that his boat would withstand any seas and that the vessel would be completed in 60 days, then sail for Monrovia Liberia.

In 1918, the News-Pilot reported that Lewis experienced difficulties in securing materials for his concrete ship. At the time, the keel was laid and part of the frame was built. He was quoted saying the ship would be 100 feet in length with a 30-foot beam when it was completed and claimed to have successfully built eight of this design. However, the local lumber yards refused to sell him the lumber he asked for saying they did not like to see him waste his money. Critics believed the boat would never get out of the harbor. For his part, Lewis said he was an old concrete construction worker and that his boat would withstand the seas. A decade prior, he was indeed a cement worker. At the time of the reporting, he announced he would complete the ship in 60 days and set sail for Monrovia Liberia.

Aside from being hindered by local contractors from securing materials, the land he was building the ship was leased right from under him by the newly formed port to J. Kohara, a Japanese machinist.

At various times the mainstream press tried to paint Lewis as a swindler, a cult leader, and even a child rapist. As time wore on, the allegations were never substantiated or were proven outright false. In regards to the first two accusations, the nascent Black community of 1920s and 1930s San Pedro supported him. Some held positions in the Ethiopian-American Steamship Company; he was invited to speak in local churches such as Mount Sinai Baptist Church about his company and the missionary work he wanted to see manifest on the African continent.

In the mid-1920s, a 10-year-old adolescent white girl was reportedly lured into a vacant lot by a “big Black man” and beaten into a state of unconsciousness. A bus driver claiming to have witnessed the attack pointed the finger at Lewis. According to contemporaneous reports was not in town at the time of the time of the assault. The nearly 50-year-old pastor sent his wife away, fearing for her safety, and endured scrutiny from jail until the young victim exonerated him of the assault. According to contemporary reports, he made good use of his time preaching to his fellow inmates and possibly converting a single soul to Christ.

Following his exoneration, Lewis resumed the work of acquiring ships for the Ethiopian-American Steamship Company through the 1930s. But by the 1940s, Lewis was just a distant memory consisting of an eccentric Christian pastor vying for the title of Noah and his ill-fated ark.

Rev. Lewis died in 1951 in Bowlin-Grace Sanitarium ― a facility owned and operated by a prominent Black Guyanese doctor, for whom the facility was named in Watts. Neither Garvey nor Lewis finished the mission their creator gave them. Though Lewis and Garvey were mocked and sometimes slandered, their obedience rather than their successes was the point.

It could be argued that among the many seeds Lewis and Garvey were able to sow, the fruits of one or two seeds could be seen in the facilitation of the June 2024 meeting of the royal delegation from the Delta region of Nigeria and the Port of Los Angeles, followed by a boat tour of the harbor.

The delegation, led by the king of the Warri kingdom in the Delta state of Nigeria, Ogiame Atuwatse III, and the top members of the African Diaspora Foundation and Aivlys LLC met with Port of Los Angeles executive director Gene Seroka. The port director explained that the topics of discussion were trade relationships and friendship.

Joe Gatlin, the CEO of Gatlin Enterprises and chair of the U.S. section of the African Diaspora Foundation, was a key figure in linking the port director and the Nigerian royal delegation. Western powers and now China still have the hands-on African resources and the diaspora is still seeking freedom and self-determination, and many still see connecting with like-minded Africans and peoples of African descent as the key to that freedom.